Last summer, Denmark became the first European nation to revoke or fail to renew the residency permits for Syrian refugees after authorities said that the situation in Damascus and surrounding areas had “improved significantly”.

A year later and the actions of the Danish Immigration Service in seeking to deport hundreds of Syrian refugees faces a domestic legal action. If this case is unsuccessful, then it could bring the Danish government before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

Around 1200 Syrian refugees from Damascus are currently living in Denmark. As there are currently no formal relations between the Danish government and Syrian regime, then these currently settled refugees could find themselves trapped in detention centres, indefinitely awaiting deportation. The livelihoods of women and children are believed to be most compromised by the policy as Danish authorities recognise that Syrian men are at risk of forced conscription or punishment for its avoidance.

The decision to classify Damascus as safe has received widespread criticism, both domestically and internationally, for its disregard for the lives of those who could face violence should they return and erroneous depiction of the security situation on the ground. In a joint letter released in April of this year, a number of researchers and analysts at Human Rights Watch said that: “We believe that conditions do not presently exist anywhere in Syria for safe returns and any return must be voluntary, safe, and dignified, as the EU and UNHCR have clearly stated.”

Charlotte Slente, Secretary general of the Danish Refugee Council, shared a similar position, stating that: “The Danish Refugee Council disagrees with the decision to deem the Damascus area or any area in Syria safe for refugees to return to – the absence of fighting in some areas does not mean that people can safely go back. Neither the UN nor other countries deem Damascus as safe.”

“It is pointless to remove people from the life they are trying to build in Denmark and put them in a waiting position without an end date,” Slente said. “It is also difficult to understand why decisions are taken that cannot be implemented.”

The case against the Danish government is headed by Guernica 37, a London-based chambers specialising in transitional justice and the defense of human rights which is challenging the policy under the principle of “non-refoulement”. According to this core principle of the Refugee Convention, no one can be returned or removed to a country where they would face torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and other irreparable harm.

“The situation in Denmark is deeply concerning. While the risk of direct conflict-related violence may have diminished in some parts of Syria, the risk of political violence remains as great as ever, and refugees returning from Europe are being targeted by regime security forces,” Guernica 37 said.

“If the Danish government’s efforts to forcibly return refugees to Syria is successful, it will set a dangerous precedent, which several other European states are likely to follow.”

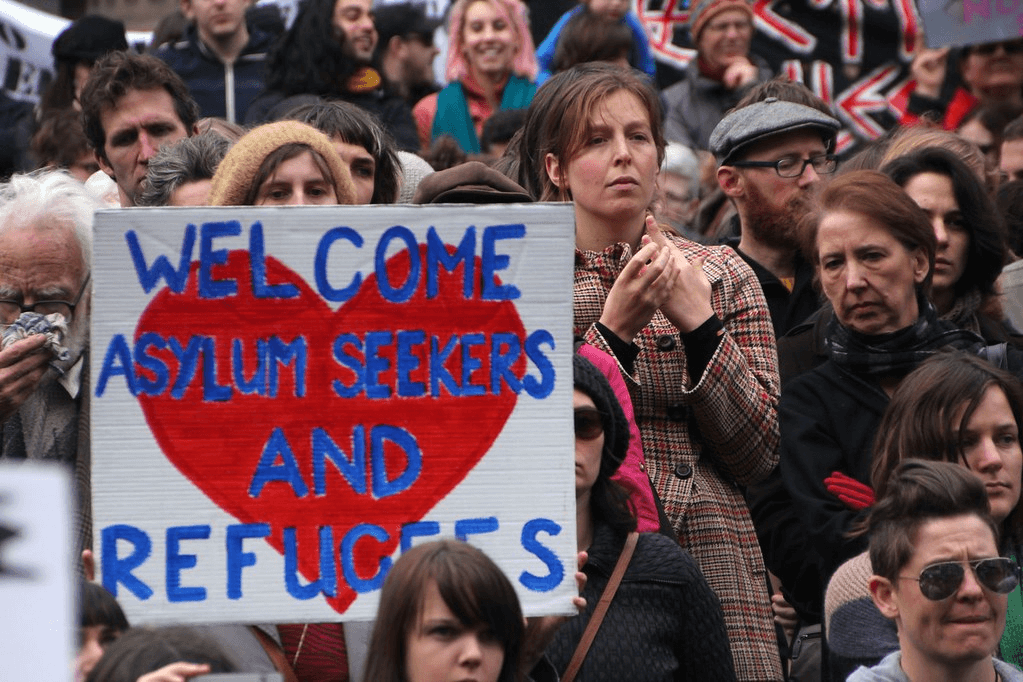

Once renowned for its tolerant and receptive attitude to refugees and asylum seekers, the rise of the far-right Danish People’s party has seen the imposition of hostile migration policy which is clearly inimical to previously held values. Denmark, the initial signatory of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, is now the first country to say that law-abiding refugees can be sent back to Syria.

Despite seeing the lowest number of asylum seekers since 1998, Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, has consistently reiterated a vision of having “zero asylum seekers”, stating that “social cohesion cannot exist” with too many refugees.

As the 1951 Refugee Convention marks its 70th anniversary, the Danish government must ensure that they do not renege on their international obligations. The security situation in Damascus and surrounding areas remains volatile and any attempts to return refugees constitutes a dereliction of duty.