The importance of privacy was highlighted in two meetings of the 47th session of the Human Rights Council (HRC) on 2 and 5 July 2021. The Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy, Prof. Joseph A. Cannataci presented his guiding principles concerning the use of information in the context of artificial intelligence (AI) solutions, and discussed children’s privacy in his report on Artificial intelligence and privacy, and children’s privacy from January 2021.

Reflecting on his mandate, the Special Rapporteur said last Friday:

“Privacy has never been more at the forefront of political, judicial or personal consciousness. Little did I know how the COVID-19 pandemic, new laws, judicial rulings and controversies surrounding corporate reviews of personal data would escalate privacy exponentially into an even higher profile.”

He identified COVID-19, state surveillance, smartphones, megatech corporations and AI as essential themes in the coming years. Moreover, he emphasized that “the protection of privacy will remain forever, a delicate matter” in our technology-driven world and that

“Privacy, freedom of expression and free access to information are essential to the universal and overarching fundamental right to dignity and the unhindered development of one’s personality.”

The Special Rapporteur’s report urges to underpin the privacy of all data when using AI solutions and lists eight principles for its use: jurisdiction, ethical and lawful basis, data fundamentals, responsibility and oversight, control, transparency and “explainability”, rights of the data subjects, and safeguards. The implementation of these recommendations requires full collaboration between governments, civil society, the private sector, the technical community and academia.

Many delegations stressed the importance of privacy rights and human rights to mitigate the negative effects of AI, such as the European Union:

“Consciously or not, the use of artificial intelligence algorithms affect our lives every day. Given that such technologies rely on data, including personal data, protecting the right of privacy and other human rights in the design, development and deployment of such technologies is critical.”

Also Liechtenstein attached “utmost importance to the right of privacy”:

“Technological advancements like AI solutions offer benefits but also have the ability to impact people’s lives in various ways, some of which infringe upon their human rights. We therefore consider it important to address the development regulation and new technological solutions with a human rights based approach to ensure that the right to privacy and the human rights are effectively protected.”

Special Rapporteur Cannataci praised Korea for its good practice of being willing to revise its own approach:

“Korea has shown that the way to tackle privacy, even in situations like COVID-19, is not to prepare regulations, however well-thought they thought they were, and then try to implement them and always say we are right, we are right, we are right. (…) Korea saw that they were being too intrusive on privacy and by August of 2020 – eight months more or less after those regulations were put into effect – the Korean institutions took a whole deal of measures to try to make the COVID measures less intrusive.”

Children’s privacy was the second main theme of the report, with the need for balance between the protection of children and their rights to privacy at the centre. The report encourages self-determination and child-centred risk assessments, and warns that the adult’s interpretation of the child’s privacy needs could impede autonomy and independence.

The report concluded by calling for the promotion of children’s privacy and their autonomy. In this regard, children need to be acknowledged as the bearers of their rights to privacy, and children’s views need to be incorporated in strategies for privacy. The report also encourages partnerships with civil society and industry to co-create technological offerings in the best interests of children and young people.

However, the Holy See disagreed with the Special Rapporteur’s guidance on children’s rights versus parent’s responsibilities. The delegation expressed its concern regarding the negative approach adopted:

“Instead, a positive approach is needed, one that embraces and supports the constructive and necessary role of parents in protecting and integrating the children. Moreover, the Holy See would like to reiterate that international law does not recognise a so called right to reproductive sexual information services, which implies access to abortion and family planning services. In addition, the mandatory parent notification and/or concern for prescribed contraceptives and abortion is not an infringement on the right or the privacy of children, but rather the right and duty of the parents in their evaluation of the best interests of their child.”

The protection of privacy rights of children was also addressed by various other delegations. UNICEF shared their concerns on the collection of personal data on children by online advertising companies, and other techniques aimed at influencing children’s behaviours and decisions. With the need for taking the circumstances, the view of the particular child and his or her best interest into account, UNICEF joined the Special Rapporteur’s call on states to ensure that

“the processing of children’s personal data does not result in violations of their right to privacy, harm their mental health or result in commercial exploitation.”

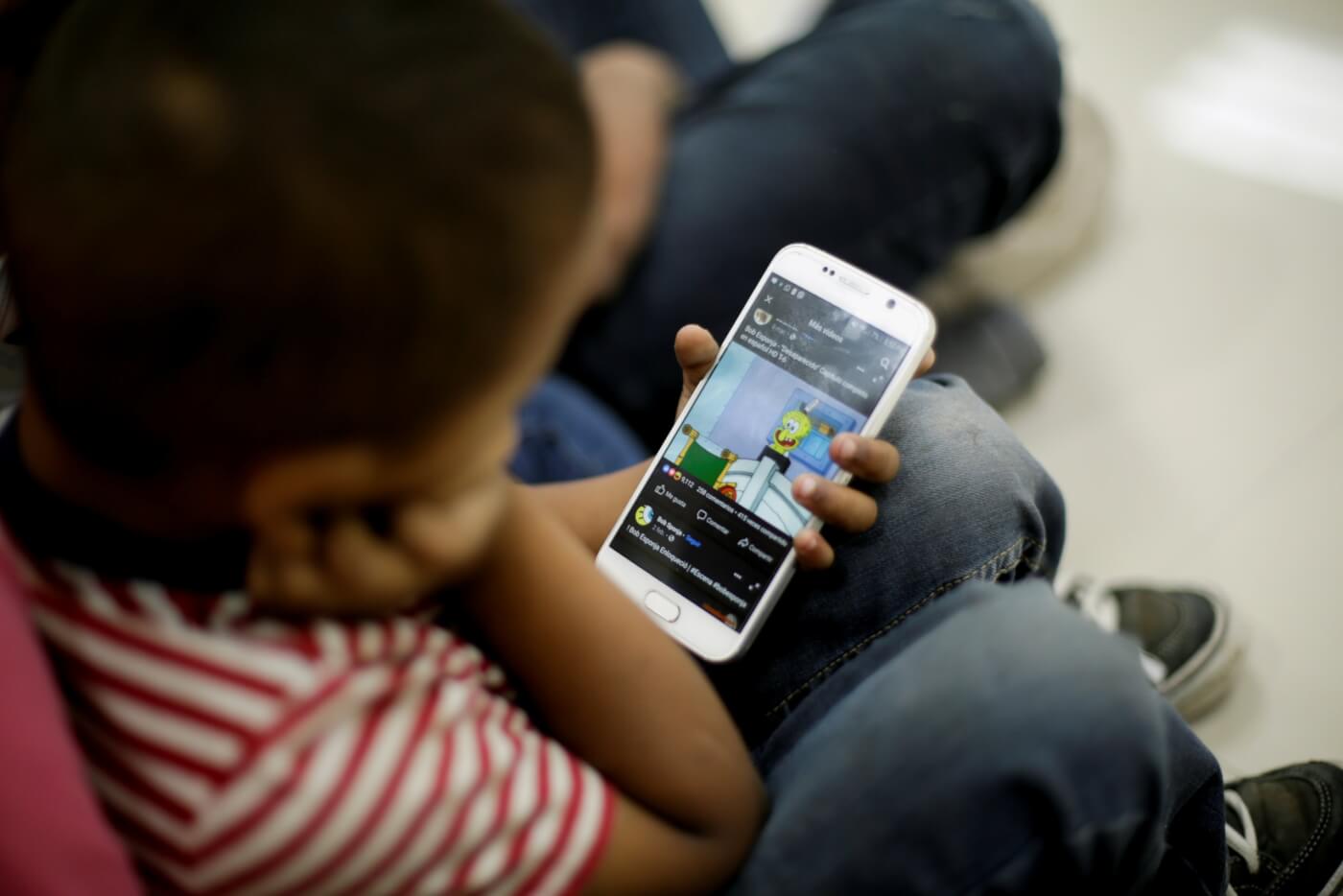

The statement by Ecuador focused on the current generation of children growing up with technology and the importance it has in their lives:

“Children and young people today are the first generation who are born in the digital era, and the parents are the first in bringing up digital children. Children and adolescents use the internet in a widespread manner, as well as social networks as a means of accessing information, their education systems, communication, leisure, social interaction, and building an identity with the consequent benefits and threats that that represents.”

The Special Rapporteur pointed out the differences of autonomy allowed to children in different countries, by highlighting the different ages of criminal liability and civil responsibility of children around the world. His main recommendation to prevent misuse of technology by children remained education from a young age:

“Digital citizen education has got to be started from the minute that kids start touching tablets, smart phones and laptop computers (…) from the ages of five or six at the very latest. (…) Do they know the extent to which they are being manipulated? Do they know the extent to which their every click is being followed for advertising reasons, for profiling reasons? They don’t and the sooner they are taught about it, the more tech-savvy they will be.”

In the continued session, the ethical aspect of AI – in particular the problem of discrimination – was brought up by many delegations. For example, Venezuela reiterated its concern at the misuse of new information communication technologies, which may endanger the right to privacy:

“Expansion of technology and the participation of transnational actors in online activity have created spaces in which privacy is extremely vulnerable. It is necessary that the development of AI solutions and algorithms in social networks do not promote racism, racial discrimination and other related forms of intolerance. Online privacy must enable protection from violence and discrimination on gender grounds.”

The Australian Human Rights Commission called for urgent action and a moratorium on the potentially damaging use of facial issue technology in Australia:

“Artificial intelligence promises to enable better smarter decisions but it can also lead to real harm and it can threaten people’s human rights. AI can create new forms of discrimination and unfairness, and whether reasoning behind AI is opaque the right to a remedy for the violations can be impossible to achieve.”

One of the main recommendations mentioned by Prof. Cannataci to tackle the problem was to promote privacy engineering in national educational systems in order to be able to embed privacy and human rights at the design stage in AI systems:

“The problem with privacy is – at the technical level – that very often privacy unfortunately historically has been an afterthought. It is something that people would like to vote on after they design a system, rather than trying to embed privacy at each and every stage. “

Instead of contributing to the discussion on privacy, the Russian Federation used its speaking time to complain about the late submission of country reports and the violation of the code of conduct by the Special Procedures:

“We find it unacceptable, where a Special Rapporteur, who has carried out six country visits, hasn’t provided one single report on the results of the visits in due time. There’s hardly any point in discussing a report, if it’s four years old, since it’s already out of date. (…) We can wonder what happened to the funds allocated for the preparation of the reports in each accounting period? Where did the resources for the preparation of the six reports come from this year? We do hope that one of these days we’ll get answers to these questions. (…) This is happening more frequently, in many cases because of the council turning a blind eye and maybe it’s time for a frank, open discussion of accountabilities as set down in Article 15 of the code of conduct.”

In his concluding remarks, the Special Rapporteur defended his mandate and condemned Russia for spreading false information:

“The intervention of the Russian Federation was a classic example of an intervention which had the cheek to speak of accountability, but was only a shield as the country pursued its own agenda which has absolutely nothing to do with the protection of human rights. Quite the opposite.”

The Special Rapporteur faced particular criticism for his report but in his summing up he stood up for his work stating,

“I very firmly stand by all my findings and recommendations. They are based on evidence based thinking we collected, and recommendations which are truly respectful of different cultural traditions, including religious ones, but they place human rights above all else in an approach aimed at reinforcing the universality of basic rights like privacy.”

He was particularly vexed at an earlier disagreement with the HRC itself over a procedural point and the timing of session,

“The council failed to give priority to substantive discussions about privacy, again (…) the world witnesses the number of countries so concerned with procedural wrangling, where they focus on substance (…). Not only does the council show disrespect to mandate holders like myself, by advocating a ridiculously inadequate amount of time for the presentation and discussion of reports, but also in allowing the debate to proceed the way it does.”

This point was aimed at China who’s delegation grandstanded by not discussing privacy matters but instead lashed out at the US,

“Asians and people of Asian descent are living under the threat of racial discrimination and hate crimes in the US. Furthermore, the US out of its political motives have slandered and smeared other countries under the guise of human rights in an attempt to interfere with other countries internal affairs”

In closing though Prof. Cannataci again berated the assembled participants saying,

“This was neither interactive nor was it a dialogue. Dialogue is a two way process where people listen to what others have to say. It was painfully obvious that a number of delegations were not listening, not to me, not to each other but simply had points to make and they (…) were still allowed to make them and have not been held accountable for such reprehensible behaviour.”

At which point the Human Rights Council President cut him off saying he was out of time.