On 1 January 2021 China will take up its seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council – the 47 state body responsible for the protection of human rights globally. Since China was elected on 13 October 2020 the International Observatory of Human Rights has documented over 100 human rights violations in China in the run up to China’s representative taking their seat on the council.

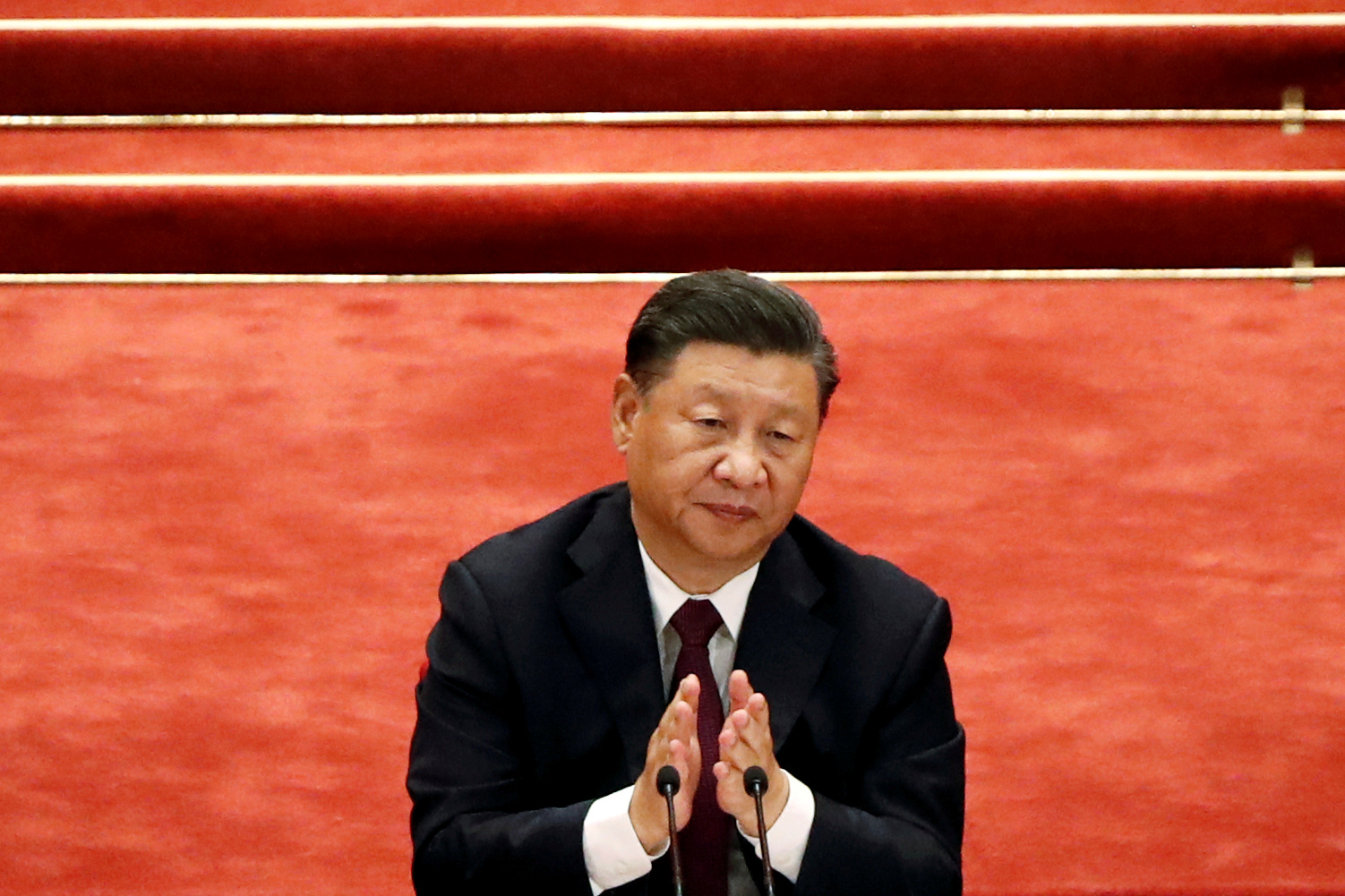

Speaking at the UN 75th General Assembly in September, Chinese President Xi Jinping addressed his peer group of leaders saying,

“Let us join hands to uphold the values of peace, development, equity, justice, democracy and freedom shared by all of us and build a new type of international relations and a community with a shared future for mankind. Together, we can make the world a better place for everyone”

Valerie Peay, Director of the International Observatory of Human Rights, commented

“2021 will give China the opportunity to deliver on the promises of President Xi for equity, justice, democracy and freedom. As a member of the Human Rights Council they are subject to transparency of their actions and responsible to the UN if they fail to reverse their current dire human rights record.”

Attack on Academic Freedom

Freedom of academics is a contentious issue in China. With constant tensions between China and other world powers, particularly the US, academics often bear the brunt of tit-for-tat moves as part of broader international feuds.

In October, Beijing threatened to arrest American academics in retaliation for a Chinese scientist being charged with US visa offences. Threats were made via multiple channels, including the American embassy in Beijing, demanding the US drop legal proceedings against the scientist and several Chinese scholars. In response, the US cautioned against travel to China not just because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but because of the dangers of “arbitrary enforcement of local laws” to “gain bargaining leverage over foreign governments”. Detaining US and other foreign citizens or imposing exit bans without due process is a form of hostage diplomacy, often used by hostile governments as leverage against each other.

Academic freedom is not only limited for foreign citizens, but internally as well. Recent years have seen an increase in the amount of professors in China who have been dismissed, arrested or even sentenced to prison after being turned over to the authorities by classroom informants for “inappropriate speech”. In November, Chinese historian Shen Zhihua was delivering a live-streamed speech at an academic seminar on the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, but was cut off an hour into the lecture for reasons which remain unclear. However, the university blamed a malicious tip-off by students who report on academics that are expressing views perceived to be in opposition or in challenge to the Communist Party and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The previous month in October, Beijing authorities detained publisher Geng Xianon and her husband on suspicion of running an “illegal business operation”, after she publicly supported a former Tsinghua University scholar Xu Zhangrun, a critic of China’s leaders who is now under house arrest. Xu Zhangrun had spent six days in police custody in July before being released. He had criticised the Communist Party in a series of recent essays, and had been barred from teaching at Tsinghua University a year ago for speaking out against the removal of presidential term limits. He was placed under house arrest earlier this year after publishing an article criticising Xi Jinping’s handling of the COVID-19 outbreak. Geng Xiaonan, as well as supporting Xu Zhangrun, had advocated for the release of a Chinese journalist who went missing after reporting on the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, and thus attracted unfavourable attention.

Media Freedom

This year, China ranked 177th out of 180 countries on the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index. Restrictions on media freedom were already poor, but were exacerbated by the dangers of reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic.

A number of journalists have been detained or reported missing after reporting on the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Zhang Zhan, a former lawyer and now citizen journalists, has been detained for over six months. According to her lawyer, she is being fed forcibly from a tube inserted in her, and her arms are restrained to stop her pulling it out, after she went on hunger strike to protest her detention. She was accused of “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble” for reporting on the outbreak in Wuhan in March. Zhang had previously been detained in 2018 for similar accusations and in 2019 for voicing support for Hong Kong activists. She denies her charges, and told her lawyer that the information she gathered in Wuhan came first hand through residents.

Zhang is one of four journalists detained this year for reporting on the COVID-19 outbreak. Chen Quishi, another former lawyer turned journalist, was detained in January and has been reported missing since February. His whereabouts is unknown, but a friend uploaded a Youtube video in September stating that he is in “good health” but under government supervision. Lin Zehua, a citizen journalist, was reported missing after reporting on the COVID-19 outbreak but reappeared in April. Wuhan businessman Fang Bin, who also reported on COVID-19, also went missing in February and his whereabouts remain unknown.

As of 1 December, China jailed at least 47 journalists this year (CPJ data). The International Observatory of Human Rights calls on China to release the journalists currently behind bars, and reverse the restrictions on media freedom. Given the spread of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, independent and accurate journalism is more essential than ever, and Chinese journalists should be able to report without fear of repercussions.

China will officially take its seat on the Human Rights Council on 1 January 2021. What will its new year’s resolution be?