A 4-year-old Canadian girl has been repatriated from a detention camp for relatives of suspected Islamic State fighters in North-Eastern Syria, though her Canadian mother has been blocked from accompanying her.

The girl, returned through the efforts of her aunt and Peter Galbraith, a former US diplomat, had spent half of her life in a squalid detention camp following the fall of the Syrian element of the Islamic State in 2019.

The Canadian government has said that they provided consular services to the girl but stressed that they had no role in securing her release. In a press conference, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that:

“The federal government facilitated the travel documents but this was something that was done by the family involved.”

The repatriation of this girl is the first time a Canadian child has been returned since a 5-year-old, known as Amira, was freed last October; though at the time, Prime Minister Trudeau called the case an exception, not a precedent.

Rights advocates have welcomed the move, yet the refusal to admit her mother has been criticised for contravening international law, specifically the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The convention states that a child should not be separated from their parents, except when:

“competent authorities subject to judicial review determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child”

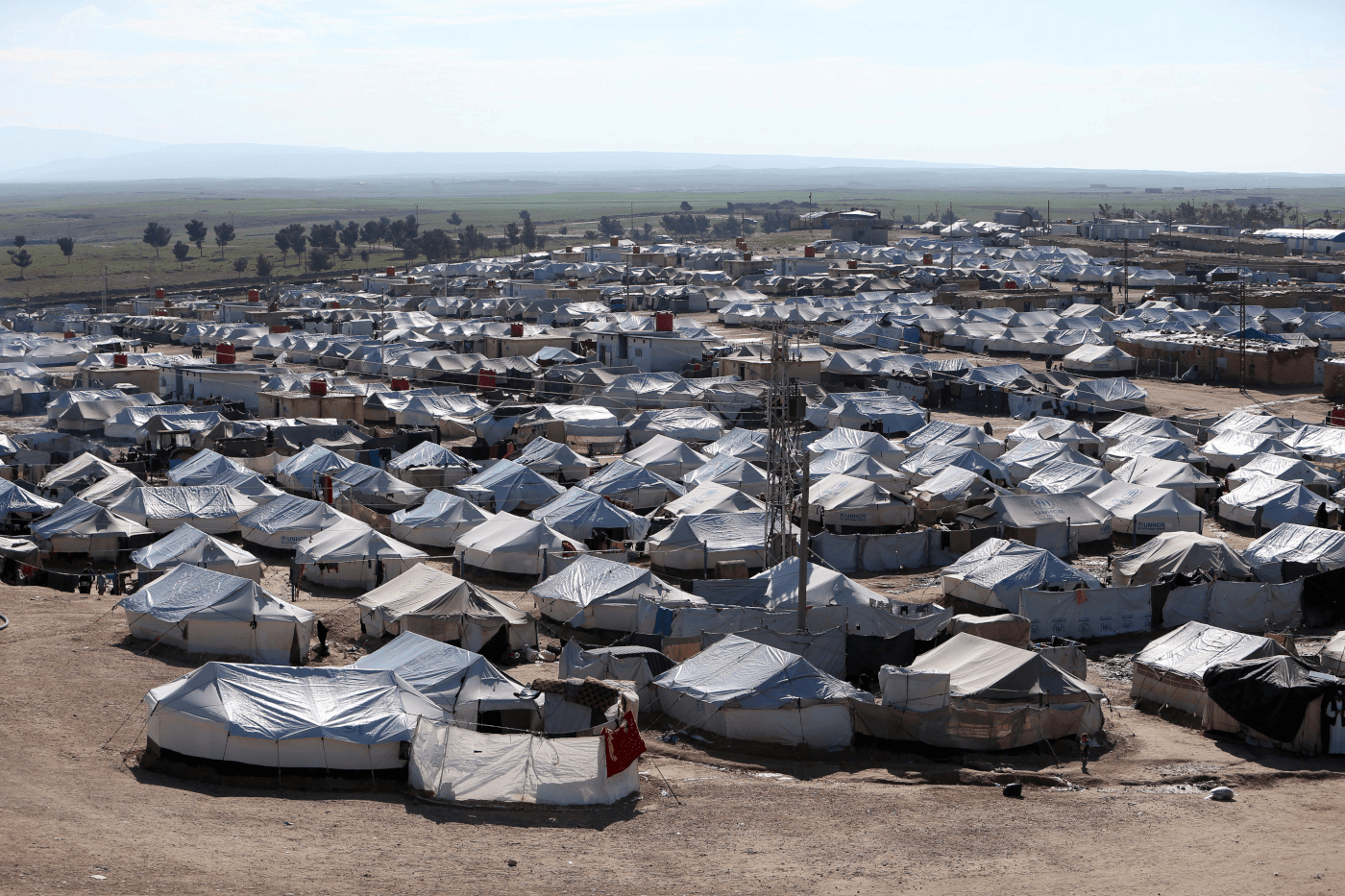

Canada and many other Western nations have recently come under intense pressure to repatriate their citizens, with detention camps in North-Eastern Syria infamous for their dire conditions and facilitation of radicalisation.

Following a deadly fire at one such camp in late February 2021, Ted Chaiban, UNICEF Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa, said that:

“Children in Al-Hol are faced not only with the stigma they are living with, but also with very difficult living conditions where basic service are scarce or in some cases unavailable”

A report published by Human Rights Watch in June 2020 found that at least 47 Canadians, including 26 children, remain stranded in Kurdish camps. The report adds that inadequate action to determine the “legality and necessity” of detention renders long-term captivity both “arbitrary and unlawful.”

According to an EU internal document, around 600 European children are currently stuck in Syrian camps and prisons, potentially creating a “new hotbed of Islamist violence”.

Kurdish authorities have repeatedly urged countries to repatriate their citizens, stating that they do not have the resources to hold them indefinitely – at least 13 French jihadists have already escaped their custody.

In December 2020, Germany and Finland repatriated their citizens, bringing back five women and 18 children from Kurdish camps. Despite this, many Western nations maintain reservations about replicating this approach, citing potential security risks.

While the repatriation of this girl is a step in the right direction, the number of children stranded in these camps remains far too high. Children must always be viewed as victims and Western nations have an obligation to secure their return in compliance with international standards. Leaving children to languish in camps that are notorious for poor medical care, pervasive radicalisation and incessant violence constitutes a dereliction of duty.