The Turkish regime has been lambasted in Human Rights Watch’s World Report 2021 for using the COVID-19 pandemic to continue its assault on human rights and the rule of law.

Almost exactly a year on from Turkey’s Universal Periodic Review, a mechanism by which UN member states have their human rights record evaluated, the new report by the New York-based watchdog further demonstrates that the human rights situation in Turkey has worsened over the past 12 months.

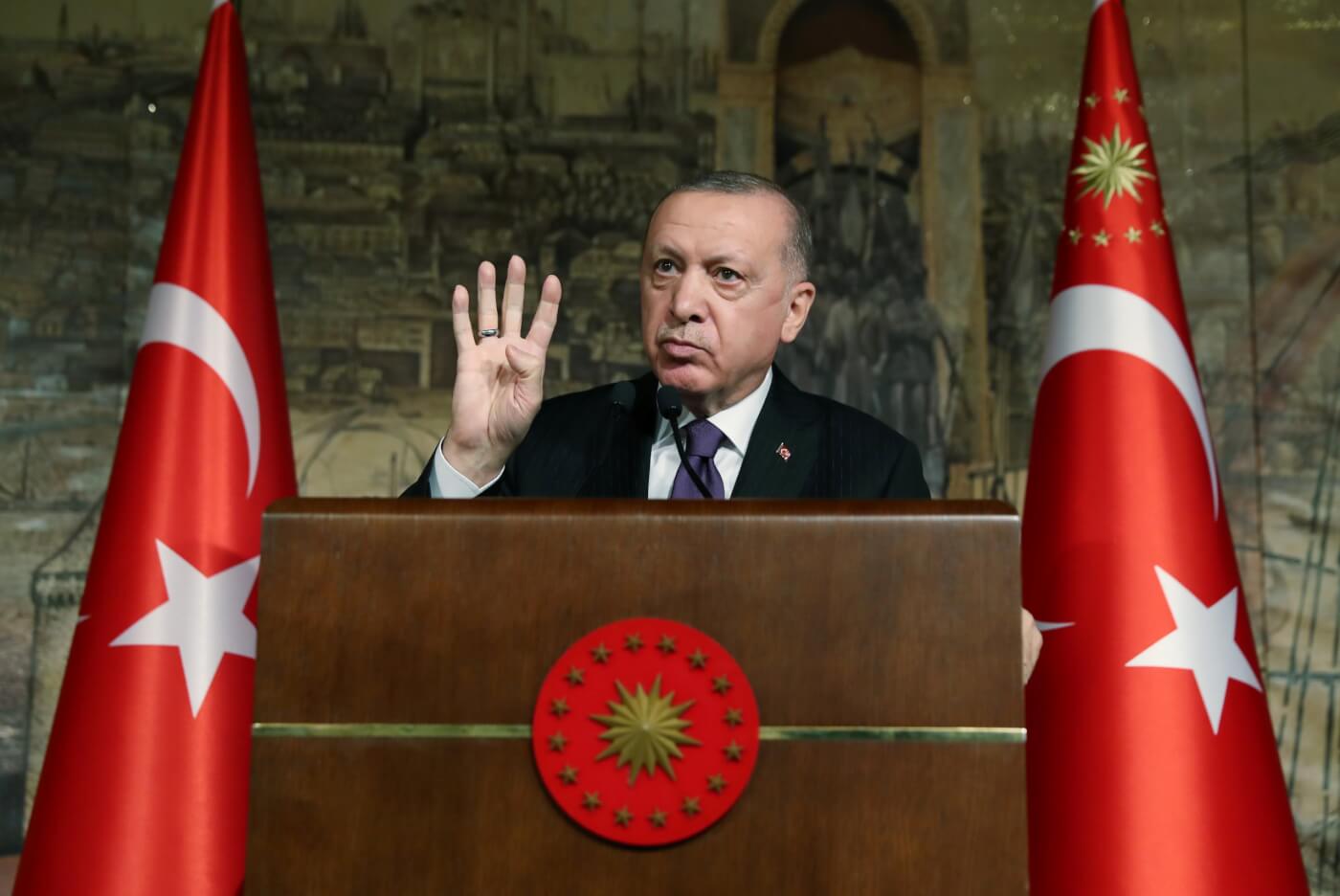

Since 2016 and a failed coup attempt, the Erdogan regime has consistently and arbitrarily targeted dissidents, journalists, human rights defenders and members of civil society to cement his grip on power.

Throughout 2020, prominent figures critical of the regime remained detained. Among those still detained are Osman Kavala, a human rights defender; Ahmet Altan, a writer; Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ, former co-chairs of the opposition Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

Over the course of 2020, in collaboration with the Turkey Tribunal, the International Observatory of Human Rights released a number of reports documenting the human rights abuses being committed by this regime. This included reports on the state of torture in turkey, enforced disappearances, press freedom and impunity.

Human Rights Watch rightly identify a number of pressing human rights issues in their report; the continued repression of opposition parties, the lack of checks on power, executive interference in the judiciary, and its involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

However, in contribution to Turkey’s last Universal Periodic Review, the International Observatory of Human Rights submitted a report on the issue of freedom of expression in Turkey.

One year on, and in light of the newly published Human Rights Watch World Report 2021, this article looks at some of the recent developments to freedom of expression in Turkey.

Jailed journalists

As of 15 January 2021, an estimated 87 journalists and media workers were in pretrial detention or are imprisoned as a result of fabricated ‘terrorism offences’, contributing to Turkey’s ranking of 154th in Reporters Without Borders (RSF) 2020 World Press Freedom Index.

Turkey is the world’s biggest jailer of professional journalists and the average journalist spends longer than a year in pre-trial detention.

Journalists are routinely subjected to long jail sentences, illustrated at the close of the year when well-known journalist Can Dündar was sentenced to more than 27 years in prison on charges of spying and abetting a terrorist organisation.

Another example is that of Mehmet Baransu. In July 2020, Baransu was handed a 19-year sentence, followed by a 17-year sentence in November. In total, Baransu could face nearly a thousand years in jail as a result of scores of cases being brought against him by the Turkish regime.

RSF note that it is not unheard of for journalists to spend life imprisoned, “with no possibility of a pardon.”

The internet and the new Social Media Law

In July 2020, Turkey passed a controversial new Internet law which, through increased regulation of tech companies such as YouTube and Twitter, poses drastic threats to freedom of expression.

As part of the legislation, social networks with more than a million unique connections per day must have a representative in Turkey; platforms will have to remove content upon court order; and massive fines and the reduction of bandwidth capacity will meet noncompliance.

Upon the law passing, ARTICLE 19’s Head of Europe and Central Asia Sarah Clarke said:

“The Turkish Government is attempting to blackmail tech companies into accepting their proposals. They face either becoming the long arm of the state censorship or having access to their platforms slowed so much that they are in effect blocked in Turkey.

These proposals are particularly dangerous given the erosion of the rule of law in Turkey under the current government. Tech companies cannot rely on the courts to challenge blocking decisions or requests for user data.”

The Human Rights Watch’s World Report 2020 states that:

“Thousands of people face arrest and prosecution for their social media posts, typically charged with defamation, insulting the president, or spreading terrorist propaganda. In the context of Covid-19, the Interior Ministry announced that hundreds of people were under criminal investigation or detained by police for social media postings deemed to “create fear and panic” about the pandemic. Some of these postings included criticism of the government’s response to the pandemic.”

The Turkish regime has also put considerable effort into persuading Turkish citizens away from the popular messaging application WhatsApp, and towards the local application Havelsan. Many human rights organisations and media professionals are concerned the app could be used to help Turkish authorities tighten their grip on internet censorship and spy on users.

News Agencies

A major casualty since the failed coup in 2016 has been independent news agencies and media outlets.

The Turkey profile on RSF’s 2020 World Press Freedom Index reads:

“After the elimination of dozens of media outlets and the acquisition of Turkey’s biggest media group by a pro-government conglomerate, the authorities are tightening their grip on what little is left of pluralism”

Over the course of 2020, the Radio and Television Supreme Board (RTÜK), Turkey’s official media regulatory body, imposed arbitrary fines and temporary suspensions of broadcasting of media outlets such as Halk TV, Tele 1 TV, and Fox TV, which include content critical of the government.

The start of 2021 seems to have seen the trend continue with Turkish authorities raiding Etkin News Agency and arresting reporter Pınar Gayıp on 14 January 2020.

The Committee to Protect Journalists report:

“During the raid, police broke the front door of the news agency’s office and searched its premises, seizing camera memory cards, computer hard drives, and 6,600 Turkish lira (US$893) in cash from the office, according to those reports.”