New research suggests that more than half of Mumbai slum residents may have COVID-19. A sample of 7,000 people taken from three areas in India’s commercial capital found that 57% of residents had been exposed to the novel coronavirus.

The survey was carried out by the city’s municipality, alongside the government think-tank Niti Aayog and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research.

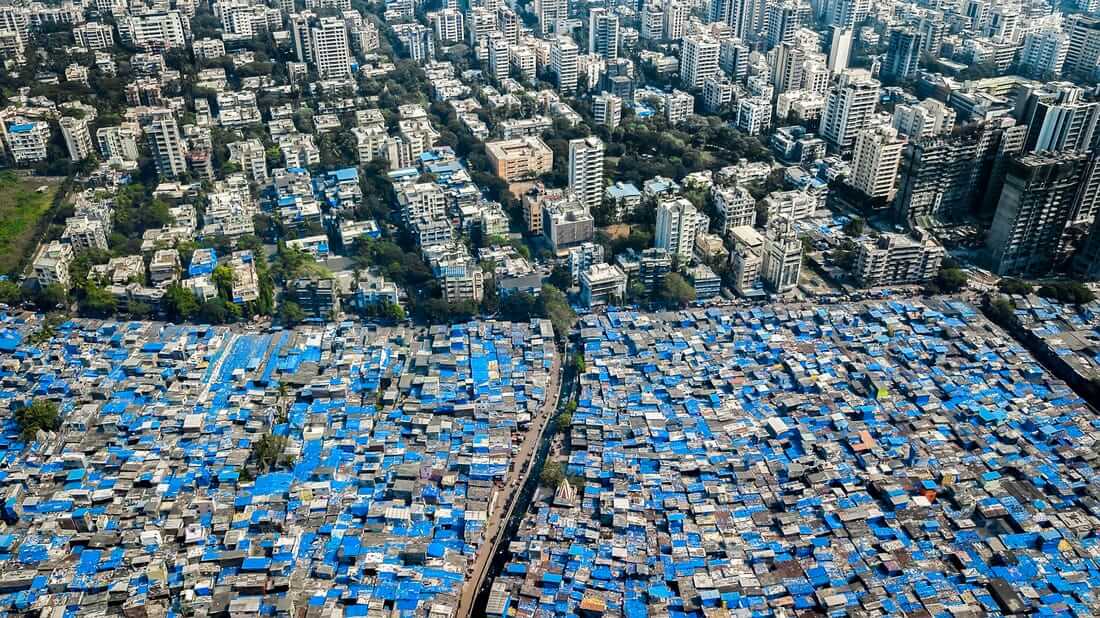

Residents were randomly tested in the slum areas of Chembur, Matunga and Dahisar, which collectively boast a population of 1.5 million people. If the findings of this survey are representative of the broader picture, then some 855,000 residents of these areas have been exposed to the deadly virus.

This is in stark contrast to the comparatively low figure of confirmed cases put forward in official figures. As of 28 July 2020, Mumbai had reported just over 110,000 cases with 6,187 deaths.

Despite the disparity between the official figures and the results of the survey, the scientists involved believe the sample tested was “statistically robust” and representative. This raises the question of what more can be done to ensure vulnerable populations have adequate access to testing, widely accepted as essential in any fight against the virus.

The study also found that only 16% of those living outside of the slum areas in Mumbai had been exposed to the virus, once again illustrating how the virus disproportionately spreads through vulnerable communities. This correlates to overcrowded, unsanitary conditions which mean basic counter measures such as social distancing, isolating and basic sanitation become much harder.

Dr Ullas S Kolthur of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) told the BBC:

“The three areas we chose for the tests had a varying number of reported coronavirus infections, and they were a mix of slums and stand-alone houses and housing complexes. The idea was to see whether population density was driving changes in the prevalence of infection,”

While the scientist fell short of saying the survey was representative of the whole city, Dr Sandeep Juneja, also of TIFR, said:

“We believe the prevalence rate in other areas should not be terribly far away from the numbers in the survey,”

Comparative studies in other big cities around the world have found significantly lower prevalence rates among their populations.

A study in London found that one in every six residents (16%) tested positive for antibodies. New York City had a slightly higher prevalence rate with one in five (20%) testing positive. These studies were conducted in May and July respectively.

A survey in Delhi, India’s capital and second most populous city after Mumbai, found that nearly one in four (25%) residents had been exposed to COVID-19.

Those involved in the study have pointed towards slum residents sharing common facilities such as toilets as explaining the higher prevalence rates, with Dr. Juneja saying:

“The results showed how crowding plays a key role in the spread of the infection”

Interestingly, cases are now slowing down in Mumbai, with this survey raising questions about whether the city is approaching herd immunity to the infection. On Tuesday 28 July 2020, Mumbai reported 717 new infections, the lowest in three months. However, Dr. Kolthur has said:

“The jury is still out on that. For one, we still don’t know how long the immunity to the infection lasts. We will only know the answer after repeat surveys,”

The survey is due to be repeated in the same three areas in August, which will offer clues about the trajectory of the COVID-19 in the Mumbai slums.

Crucially, those involved have said that the presence of antibodies is not enough to guarantee protection against the disease. ‘Neutralising’ antibodies decide the level of immunity to the infection and some studies have found these decline in 90 days.

The best hope for the residents of these areas is the creation of a vaccine.

It will then be the responsibility of governments, international institutions and the pharmaceutical companies to ensure that, if and when a vaccine comes to fruition, it is made readily available to the vulnerable populations shown to be most at risk.

As Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations said:

“No-one will be safe until everyone is safe.”