The exponential transmission of COVID-19 is compounding the plight of some of the world’s most vulnerable people. While it took three months to reach the first 100,000 cases of the virus, it took only 12 days to double that, and in the words of Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO) “Every day, COVID-19 seems to reach a new and tragic milestone”.

Since Wednesday 18 March, 2020, the Greek government has imposed a set of stringent measures to the Greek islands migrant camps, in light of the first case being recorded in one of the “hotspots”.

On Sunday 22 March, 2020, we heard of the first confirmed case of the coronavirus in Syria, a country whose health system, housing and infrastructure has been ravaged by nine years of civil war.

While today (Monday 23 March, 2020), UK charities have warned that around one million migrants who have had applications for asylum denied are not just at risk of contracting the virus, but also face starvation as a result of the virus shutting down the services they relied upon.

Each scenario shows how refugees and asylum seekers are put at an acute risk as a result of this pandemic.

The Greek Tragedy

Last week the Schengen area closed its external borders in an attempt to stem the influx of COVID-19. The next day, the Greek New Democracy Party set up some internal barriers of its own, introducing a set of measures that would apply to the migrant camps in the Greek islands.

The five Greek island “hotspots” currently shelter around 42,000 people, and while there is yet to be a confirmed case in one of the camps, news of an infected individual on the island of Lesbos will create fears of an imminent outbreak.

As of Wednesday 18 March, 2020 the camps have been in complete lockdown from 7pm to 7am. In the daytime, only one person is allowed out per family and their movements are under the control of the police. The camps on Leros and Kos have been closed entirely.

Under normal conditions, health services are struggling to meet the demand placed on its resources as a result of this pandemic; the implications of an outbreak in these camps would be even worse.

In Moria, on Lesbos, the largest camp of the Greek islands that is temporarily home to around 20,000 people – despite being built for 6,000 – there is just one tap of water per 1,300 people, one toilet for 167 people and one shower for 242 people.

In England we have been told to stay 2 meters away from the nearest person, in Moria up to six people may be sleeping in 3 sq meters – a quarter of the size of an average parking space.

Speaking of the dangers, Apostolos Veizis, director of the medical operational support unit for Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) said:

“You are locking children, women and men into severely overcrowded camps where the sanitation and hygiene conditions are horrific… They do not have enough water or soap to regularly wash their hands and they do not have the luxury of being able to self-isolate”.

In the Midst of War

The first confirmed case in Syria raises similar concerns, with U.N. officials and humanitarian workers warning an outbreak could be catastrophic. The country’s infrastructure has been shot by nine years of intense conflict. Millions of Syrians remain internally displaced, in rampant poverty and left to survive off barely functioning medical facilities.

Medics say the country is also vulnerable with thousands of Iranian-backed militias fighting alongside Assad’s forces. Iran has been one of the countries most affected by the pandemic outside China and is Syria’s main regional ally. Despite flights from Syria being suspended, Iran’s Mahan Air still has regular flights from Tehran to Damascus, according to Western diplomats tracking the situation.

Military defectors say a number of senior officers have taken leave and in some units commanders have given orders to avoid mingling with Iranian-backed militias seen as higher risk of spreading the virus.

Of particular concern is that the coronavirus could quickly spread into crowded camps for tens of thousands of displaced Syrians who lack any capacity to fight the virus.

A total of 60 beds are now available in Syria for a Covid-19 outbreak, which aid agencies have warned leaves the three-million-strong population desperately ill-prepared.

Sonia Khush, director of Save the Children said:

“In Idlib, when our partners go and talk to [displaced Syrians] about coronavirus preparedness, they start laughing… They’re trying to find places to live, a lot of them are still in fields. Their top priority is shelter and getting things like jerry cans to keep their water. For that population coronavirus has not hit their top five concerns. They’re still dealing with basic needs.”

Today has also brought news of the first confirmed case in the Gaza strip, an impoverished enclave which, similarly to Syria, has seen its health care system deteriorate through years of conflict.

Authorities in Gaza, which has been under an Israeli and Egyptian blockade since the Islamic militant group Hamas seized power from rival Palestinian forces in 2007, confirmed that two cases of the virus had been found overnight in returnees from Pakistan.

An outbreak could wreak havoc on the Palestinian territory, which is home to over 2 million people, many living in cramped cities and refugee camps.

Furthermore, it will surely just be a matter of time before this virus finds its way to other war-torn countries such as Libya and Yemen, which are both divided by civil wars that have ruined their healthcare systems.

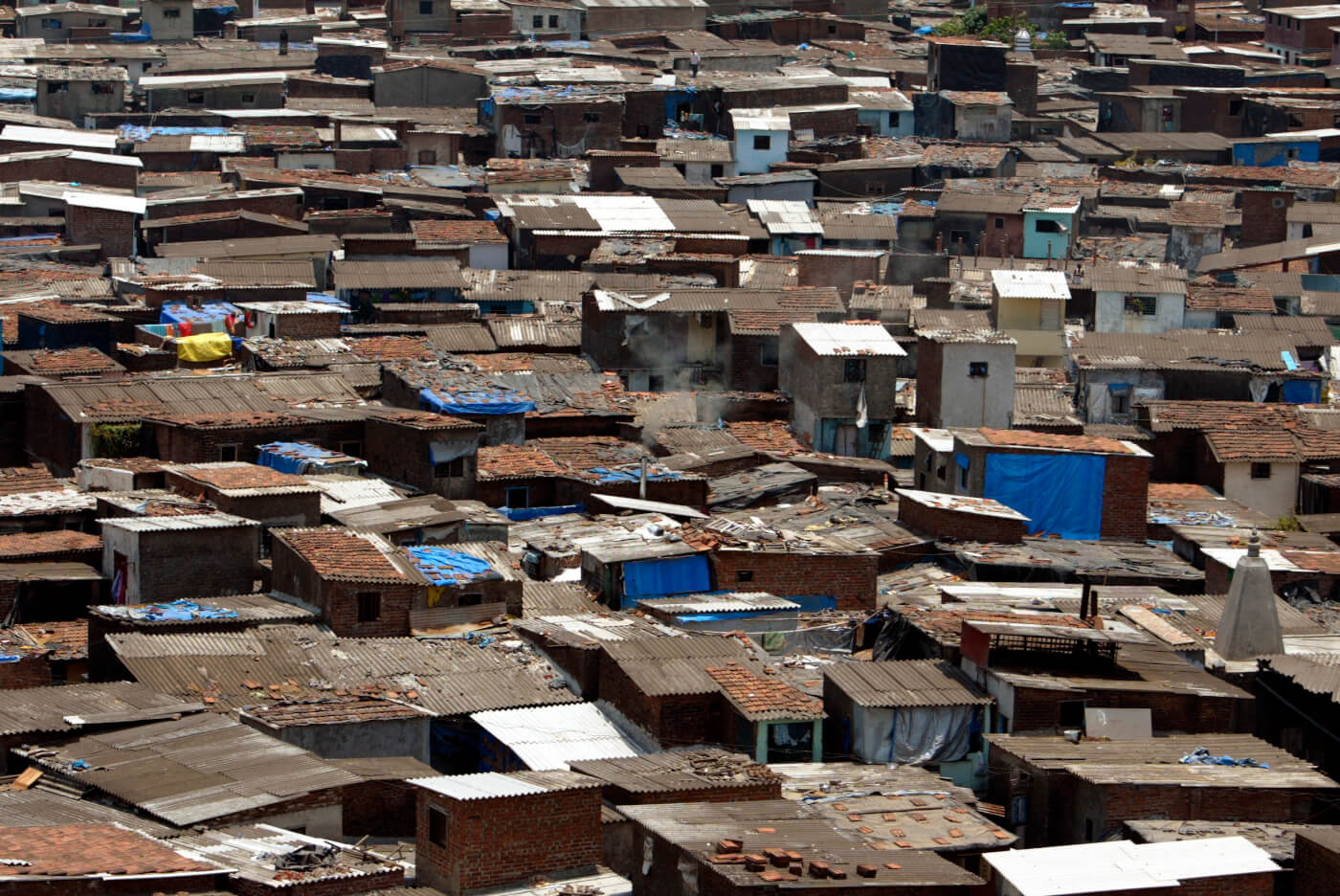

Neither are these issues confined to warzones; there is similar cause for concern for those densely populated areas in the developing world, that have far less capacity for isolation and fewer tools for tackling the virus. For places such as the Dharavi slums in Mumbai, or the Brazillian favelas, it would be near impossible to protect life in the eventuality of an outbreak.

The Unseen English Problem

In England, asylum seekers are facing a very different set of challenges, although they are at no less risk. Asylum seekers who have had the case refused receive no financial support from the Home Office.

Those who have been rejected are also not allowed to work and survive as a result of a network of charities who provide survival packages of cooked meals at day centres, food parcels, secondhand clothing and supermarket vouchers. However, these charities have been forced to close their day centres because of the pandemic.

Nobody knows exactly how many of these migrants are currently in the UK but a report published by the Pew Research Center in November 2019 estimated that there could be between 800,000 and 1.2 million of these migrants currently living in the UK.

The risk is not just that they will contract the virus, but that they will starve as a result of the pandemic on the services they relied so heavily upon.

Speaking to the Guardian Mohammed, who was refused asylum despite coming from Eritrea, where the Home Office will not send people back to, said:

“Every place where we got support is closed now. My friend gave me a bike because I have no money for bus fares. I’m cycling around everywhere looking for food but can’t find anything. If I can just find enough food to eat once a day, I think I will survive but I have not managed to find very much to eat… I’m not worried about coronavirus, I will accept whatever comes into my life with the virus. But I am worried that I will die from hunger.”.

This outbreak is challenging the way the world works as we know it, from our financial systems, our infrastructure and our everyday way of life. No one is immune to the impact of this pandemic. However, it is important now more than ever to ensure we do all we can to safeguard those who were already at their most vulnerable.