With its beautiful landscapes embroidered with ever-green olive groves, cherry orchards, fig trees, and hundreds of historical sites, Idlib attracted tourists from all over the world. I was born there in 1969, one year before Hafez Assad became President-for-life of Syria. One whole year without an Assad regime, before our carefree life in Idlib was slowly suffocated by tyranny and oppression.

The beginning of the Assad regime

After Hafez Assad came to power in a coup arranged between army officers and Bathists, Syria went through a raft of dramatic changes in politics, economics and social structure. The army was soon dominated by Assad followers, especially once he started purging officers who had refused to take part in the coup. Some were imprisoned, some were deported, some were simply killed.

To whitewash his ascent, Hafez Assad started visiting the different provinces of Syria – Idlib was on the itinerary. In 1970, the year after I was born, he visited Idlib City and tried to deliver a speech from a balcony in a grand manor in the town center – the usual populist bluster of a totalitarian dictator. Not long after he started, though, the people gathered below threw shoes and tomatoes at him. He was forced to stop and leave at once, the crowd too thick to scatter by force. He was filled with rage and hatred to this small province.

During my childhood, I was forced to glorify Assad along with all the boys and girls in school. I always heard my father attacking Hafez Assad’s dictatorship at home, but I couldn’t understand why he would be so unhappy about the man our teachers at school called the “unique eternal leader” of Syria.

In the beginning of the 1980s, Idlib Province went through difficult times as Hafez Assad suppressed his remaining opponents, both real and imagined. Public services in Idlib continued to decline, and the economy struggled, but speaking out was a quick way to become “an opponent.” Many in Idlib were killed and many more were arbitrarily arrested without any prosecution – all alleged “opponents.” Very few detainees were released in the end, as most disappeared into Assad’s prisons.

True, Idlib witnessed nothing like Hama Province, where about 40,000 were killed in a large-scale military operation against anti-regime demonstrations led by Hafez’s brother Refa’at Assad. But there were massacres in Idlib nonetheless. On the 9th of March 1980, Assad’s forces committed a horrible massacre in Jesre Al Shughour city to the west of Idlib Province. Dozens of people, suspected of being members of the Muslim Brotherhood, were put to the wall in a public square and shot dead in front of the public.

I didn’t pay much attention to this in 1987, though, when I finished secondary school full of patriotism and energy. I decided to join the Army as an officer, applied and passed all tests, and yet I was not admitted. I didn’t understand.

When I asked my father, a policeman at that time, he told me that Assad would not accept army officers from Idlib or Sunni Muslims in general. I didn’t understand that Hafez Assad played on sectarianism to stay in power. Only those who showed total submission and pledged total allegiance to Assad and his ruling figures had a chance at high positions in the government.

Hafez Assad died in 2000, but his son Bashar Assad inherited power and continued to repress the people of Idlib – perhaps afraid that opposition still lingered. Officers who were known for their brutality were assigned to work in Idlib’s four security branches – ghosts behind the scenes who controlled every single detail of people’s life.

Anger and dissatisfaction were gradually filling the hearts of people, even if they couldn’t show it. Fires burned deep under the ashes. This fire needed just one blow of wind to glimmer amidst darkness. However, like many others, I thought that Assad’s family would rule Syrians forever.

The Arab Spring and the Syrian revolution

When the Arab Spring started in Tunisia and crept over to Egypt and other Arab country, I was afraid that Syria was an exception simply because everyone knew the nature of the ruling regime. Nobody imagined that the day would come when people would revolt against Assad, with the bad memories of 1980s massacres still vivid in everybody’s mind. Yet revolution was fermenting deep in the unconsciousness of new generations, globalization bringing news of demonstrations in other lands to every small village in the country.

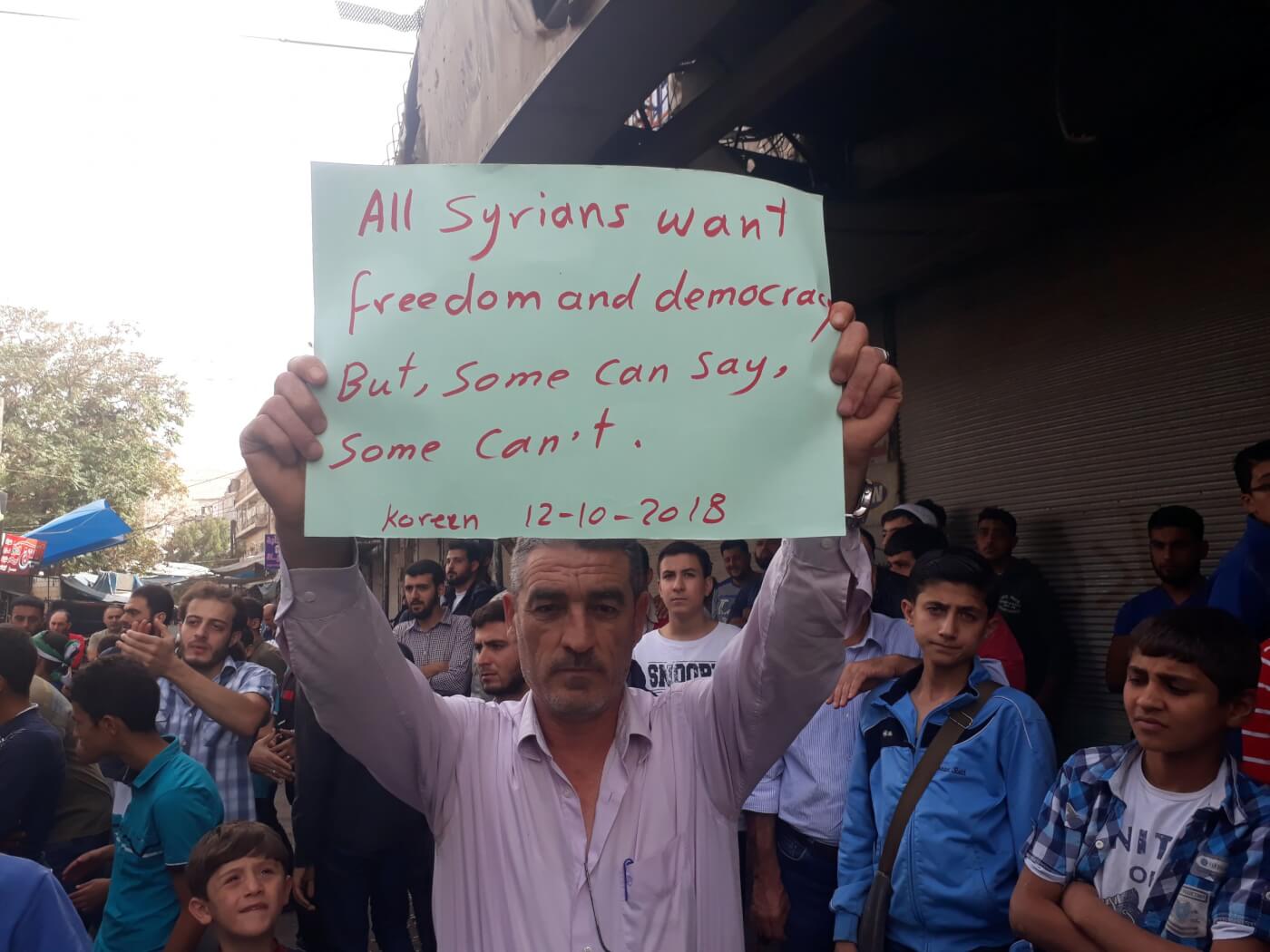

With the advent of the Syrian Revolution in March 2011, I could hardly believe that the winds of change would include Syria. Surprisingly, most villages and towns in the Province of Idlib took to the streets in massive demonstrations denouncing Assad’s regime and calling for toppling Assad himself.

The Idlib Province was the first to join Dara’a’s uprising for dignity and freedom as demonstrations started in April 2011. It was just like a ball of snow rolling from one area to another, growing as it went. People seemed to have waited for that moment for ages.

At that time, I was teaching English at the University of Aleppo. I took to the streets and demonstrated for freedom and democracy. Soon after, I was arrested by Assad’s forces on my way to the university – and then again a few weeks later. Fortunately, I was set free after I was forced to pledge to help in stopping the demonstrations in my village, which was one of the strongest opponents of Assad’s regime.

I had to stop going to university for fear of being arrested for the third, and perhaps the last time. Soon, I was fired from my job – they even fired my wife, who was also an English teacher.

Assad’s regime was alert to the danger it faced right from the beginning, and started oppressive and brutal measures against peaceful demonstrators throughout the province. However, it was in vain, as people insisted on their demands. In May 2011, Assad deployed most of his army in Idlib province. Tanks were spotted everywhere around military checkpoints. The city of Idlib was still a little calmer than the countryside as people in the countryside were angry with the regime for years of negligence and suppression. A few weeks later, though, the city of Idlib joined the demonstrations. Assad’s military and security forces grew fiercer and fiercer. The regime was aware of the sheer frustration that had engulfed people for decades.

At the beginning of the Syrian Revolution, Assad’s regime attempted to mobilize the Druze minority in the Northern countryside of the Province – the old tactics of playing on sectarianism. He sent envoys to meet social figures in the area in an attempt to convince Durzis to take arms against the increasing number of demonstrators. But all these attempts were in vain as people in the Druze villages refused to take arms against freedom seekers. When Assad’s forces started targeting villages and towns with heavy weapons, people left their homes and went to stay in the Druze villages whose people were very hospitable with the internally displaced persons.

The first massacre of Assad’s regime took place near Al Mastumah village near Idlib City on the 21st of May 2011 while demonstrators were marching from Ariha to Idlib City. Hundreds of thousands were heading to Idlib to stage a standoff in protest, but security forces made an ambush just a few kilometers south of the city. They opened fire on demonstrators. Eleven demonstrators were killed in a few minutes, and about 50 were injured. I was an eyewitness to that horrible massacre.

One week later, there were some confrontations between demonstrators and security forces in Jesre Al Shughour city. That was a landmark in the history of the Syrian Revolution, as demonstrators fought back and some soldiers defected to join them.

In 2012, the Revolutionary Movement started to change into an armed conflict as many peaceful demonstrators were killed by Assad’s forces in different areas in Syria. Armed conflict started in different areas throughout Idlib as many soldiers and officers defected from Assad’s Army – soon calling themselves the Free Syrian Army. Idlib Province paid a high price as most of Assad’s forces were deployed there.

No later than the beginning of 2013, some extremists armed factions of the opposition took control of most of Idlib Province including borders with Turkey. The new Islamic armed groups had support from regional countries like Turkey and Qatar. These extremist factions had the upper hand over the Free Syrian Army. Assad’s forces soon lost control of all the countryside of Idlib Province. They only controlled Idlib City and the road to Ariha which connects to the Western parts of the country. In 2015, rebel groups attacked Assad’s forces in Idlib City and won the battle. Idlib was under the control of opposition military factions.

More and more Islamists dominated the military and political scenes, however. They sidelined the Free Syrian Army and many adopted political agendas that sidelined the original goals of the Revolution in favor of borderline Al Qaeda priorities. That benefited Assad.

The world turned its face away from the just and fair cause of the Syrians who demanded freedom and democracy. Advocates of democracy were losing hope day after day. For me, it was a heart-breaking new situation.

Even more Islamists joined the Revolution, and their black flags started to dominate the scene. They had their own agenda, which had nothing to do with the Syrian Revolution. They were part of the international jihadi project extending from Afghanistan to Mali. Just like many other advocates of democracy and freedom, I was devastated by the domination of Islamic States in Iraq and Sham ISIS and Al Nusra, which was another copy of Al Qaeda.

With many determined freedom seekers, I went on demonstrating with the green flag of the Syrian Revolution. People like me were caught between two enemies: Assad’s regime and the Extremist groups.

Leaving Idlib behind

In 2015, Assad’s warplanes targeted my house with all its furniture. It is one small example of what happened to many Syrians. Large parts of Syria and its cities were demolished, more or less like my house was.

It is very hard to express how one feels when his or her house is destroyed with all within it. It is not about the loss of money spent on the house; it is more about the psychological stress of what it means to become homeless.

I was very lucky that I and my family were outside the house. Many other families were not. I wonder how Syrians will be able to forget these atrocities and start their life again after the war ends.

On 16th of November 2017, I and my son Ahmad, who was studying medicine at Idlib University, were going to Idlib City, where I had started to work for the Idlib Health Directorate. He was driving and I was sitting next to him. Suddenly two masked guys on a motorbike followed us. We took to the right side of the road so that they could pass, but instead of passing by, they opened fire on us. First, they started shooting at the driver, my son. They went on firing onto other windows of the car to kill me.

Six bullets penetrated the windows. It was a miracle that none of the bullets hit us, and we survived the attack.

They wanted me to keep silent, as I used to appear on TV channels from time to time to talk about the true goals of the Revolution. Though I never gave up, the worst was coming. On the 18th of January in 2019, I got in my car in the morning and drove for 200 meters away from my house when the car exploded. It was a horrible blast that destroyed the car and seriously injured me. Again, I survived, but now with shrapnel everywhere in my body.

German friends of mine were shocked by the repeated assassination attempts and helped me leave the country and get to Germany, where I live now.

The two attacks remain a mystery – it is not easy to figure out whether they were plotted by Assad’s agents or extremists dominating Idlib Province.

The current situation

While writing this in my new location in Germany, I feel unable to comprehend all that happened to me and many other Syrians. I might be very fortunate as I arrived here safely. But what about those who are still stuck in the most dangerous area on earth?

Four million locals and internally displaced people are still living in this small, disaster-stricken province, as many Syrians who had to leave other provinces came here. Idlib has become the last haven for the Syrian Revolution after Russia-backed Assad’s forces took control of other areas in the country.

In the middle of 2018, not long before I left the country, Assad’s forces invaded more areas in the south and southeastern part of Idlib Province. As a result of this military operation, many villages and towns in Abu Dhuhour and Senjar areas were occupied by the regime’s forces and their Russian and Iranian allies. Most of the civilians in these areas were displaced and the new influx of displaced people in other areas constituted an enormous humanitarian challenge for local and international organizations.

The Province of Idlib is now trapped in a real problem after fanatical Islamist groups have dominated most of it.

What remains of the liberal movements are very weak, as many politicians and public figures were forced to leave the area. Some of them are in prison. Others were killed. A very few, like me, survive – albeit often in exile.

This has provided an opening for religious extremists to dominate the scene with no patriotic tendencies to Syria itself.

All of this makes Idlib the worst place to live in on earth – encircled and soon to be entombed by regional and international conflicts that involve Russia, Iran, Turkey and other powers. All these countries have their proxies on the ground. Assad’s forces and the opposition forces are no longer in charge themselves.

At the time of writing, Assad’s air forces and Russian warplanes have continued to target most areas in Idlib Province. These military assaults have so far destroyed many hospitals, schools and other public service facilities. Half a million civilians have been displaced.

Assad’s forces are now very close to the strategic city of Mua’ret Al Nua’man on the M5 Highway to Damascus.

Because the world has turned a blind eye on what has happened in Syria, Idlib Province now faces a final destruction amid an unimaginable humanitarian crisis. With only a few of us left to try and write about Idlib, spare a thought for what once was, what might have been, and what still could be.